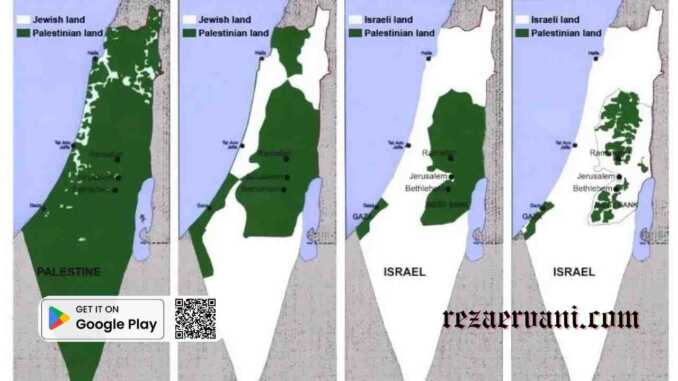

هكذا سرّبت ونزعت الأرض في فلسطين

How Land in Palestine Was Infiltrated and Seized (Part Two)

By: Rasim Khamaissi

Translated by : Reza Ervani bin Asmanu

This article “How Land in Palestine Was Infiltrated and Seized” is included in the History of Palestine Category

قسّم قانون الأراضي العثمانية الأرض إلى خمسة أنواع: الأراضي الموات، الأراضي الأميرية، الأراضي المتروكة، الأراضي الموقوفة، الأراضي المملوكة. وفقاً لهذا القانون هنالك ثلاثة أنواع من الأراضي تبقى تحت السيطرة العامة (الدولة): الأراضي الموقوفة تستعمل لأغراض دينية شبه عامة، وقد قدرت مساحتها في فلسطين بين ٧٥٠-١٠٠٠ ألف دونم، تشمل أملاك الأوقاف الصحيحة وغير الصحيحة.

The Ottoman Land Law divided land into five types: dead land (mawat), miri (state) land, matruk (abandoned/communal-use) land, waqf land, and private property (mulk). Under this law, three land types remained under public (state) control: waqf lands used for quasi-public religious purposes, whose area in Palestine was estimated at 750,000–1,000,000 dunams, covering both valid and invalid waqf holdings.

أما تسجيل الأراضي المملوكة فكان محدود، خاصة في فترة سيادة نظام الملكية المشاعية. حيث استهدف قانون الأراضي العثماني لعام ١٨٥٨ تفتيت الملكية المشاعية بما في ذلك في فلسطين. فحتى عام ١٩١٨ كانت نسبة 70% من الأراضي الفلسطينية أراضي مشاع، ثم أخذت هذه النسبة بالتقلص تدريجيا لتصل إلى ٥٦% من مجمل الأراضي الفلسطينية عام ١٩٢٣، ثم إلى ٤٦% عام ١٩٢٩ ووصلت إلى حوالي ٤٠% عام ١٩٤٠م.

Registration of privately owned land was limited, especially during the prevalence of the musha‘ (communal) ownership system. The 1858 Ottoman Land Law aimed to fragment communal ownership, including in Palestine. Up to 1918 about 70% of Palestinian land was communal; this gradually declined to 56% by 1923, 46% by 1929, and around 40% by 1940.

من الجدير بالذكر أن لنظام المشاع سلبيات وايجابيات، إذ عمل على عدم تفتيت الأراضي المشاع لفترة من الزمن استمرت حتى إقرار الانتداب البريطاني قانون تسوية الأراضي عام ١٩٢٨ والشروع بعملية تسوية الأراضي الفلسطينية. هكذا فإن نظام المشاع شكل عائقاً أمام بيع الأراضي المشاع للأجانب وخاصة للحركة الصهيونية.

It should be noted that the musha‘ system had both drawbacks and advantages; it prevented the fragmentation of communal lands for a time, which lasted until the British Mandate enacted the Land Settlement Ordinance in 1928 and began settling Palestinian lands. Thus, the musha‘ system formed an obstacle to selling communal lands to foreigners, especially to the Zionist movement.

لذا ليس من قبيل الصدفة أن عملية تسوية الأراضي وتسجيل الملكية وإلغاء نظام المشاع ركزت في المناطق السهلية في فلسطين بدءاً من الحولة مروراً في غور بيسان، مرج بن عامر والسهل الساحلي، وهي المناطق التي تمكنت الحركة الصهيونية من السيطرة وشراء الأراضي بها وإقامة المستوطنات عليها والتي تعرف بإسم ال – “N ” الاستيطاني للحركة الصهيونية، ولاحقاً شكلت الأساس لتقسيم فلسطين بعد إقرار وعد بلفور وإنجازه خلال فترة الانتداب، خاصة من خلال تسوية الأراضي وتسجيل الملكية وتمكين الأجانب من تملك الأراضي بموجب قانون الأراضي العثماني.

It is not a coincidence that land settlement, title registration, and the abolition of the musha‘ system were concentrated in the Palestinian plains—starting with Hulah, through the Beisan Valley, Marj ibn ‘Amir, and the coastal plain. These were the very areas the Zionist movement managed to control and purchase land in to establish settlements—known as the movement’s “N” colonization scheme—which later formed the basis for the partition of Palestine after the Balfour Declaration and its implementation during the Mandate, particularly through land settlement, registration, and enabling foreigners to own land under the Ottoman Land Law.

من الجدير بالذكر، أن جزء كبيرا من الفلاحين والمالكين المستعملين للأراضي من الفلسطينيين لم يقوموا بتسجيل الأراضي على أسمائهم تهرباً من الخدمة العسكرية ودفع الضرائب. مما يعني أن اعتماد سجلات الأراضي الرسمية كأساس لتحديد أو لتقدير ملكية الأراضي الخاصة للفلسطينيين هو أمر خاطئ ولا يمثل حقيقة ملكية وحيازة الأراضي الخاصة في فلسطين. ولا يمكن اعتماده لتحديد حجم ملكية اللاجئين الفلسطينيين حسب ما يتم عرضه من قبل المؤسسات الصهيونية والإسرائيلية لإنكار حق الفلسطينيين في الأراضي في مضاربهم، قراهم ومدنهم.

It should also be noted that a large portion of Palestinian peasants and land-using owners did not register land in their own names to avoid conscription and taxes. This means relying on official land records as the basis for determining or estimating Palestinians’ private land ownership is erroneous and does not reflect the reality of private land ownership and possession in Palestine. Such records cannot be relied upon to determine the extent of Palestinian refugees’ property as presented by Zionist and Israeli institutions to deny Palestinians’ land rights in their encampments, villages, and cities.

To be continued in the next part, in sha Allah

Source : Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights

Leave a Reply